Montgomery Ward Vintage 1970s Suit Dark Blue Red

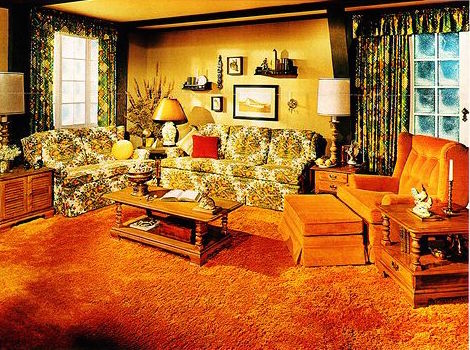

Futzing around on social media, as one does, I recently stumbled upon a meme that hit close to home. Over a picture-patterned sofa in an autumnal-colored velour with scrolling dark wood trim, it declared, "Everyone's grandparents had this couch. Everyone's." I paused, because my grandmother did, in fact, have this exact type of couch. The site TipHero took the meme further in a list associating this couch style with an "ancient" television very similar to my grandma's large floor model with turned wood in the frame. The list nailed Grandma's house in other ways: "Bonzana" on the old TV, lace doilies, tomato pin cushions, hard candies, crossword puzzles, transferware, shag-rug toilet covers, and leftovers in Country Crock tubs.

"The good news was that fabric was going to last forever—but the bad news was that fabric was going to last forever."

When I was growing up, Grandma lived in a small prefabricated Lustron house built for World War II vets on the northwest side of Tulsa. Grandpa died when I was age 5 in 1980, so my memories of him are hazy. But the couch was a part of her home as long as I could remember: It was printed with a repeating image that might have been a rustic barn with a wagon wheel perched outside or an old mill with a water wheel, surrounded by reddish orange and gold flowers, and possibly wild fowl like pheasants or turkeys. The fabric also had a fuzzy velour-type texture, but it was scratchy against the skin. And the arms, made out of scrolling dark wood covered in more of that fabric, were hard and unfriendly for leaning against.

The couch was perfectly set among the wood-paneling on the wall, the dense, rust orange carpet on the floor, the cuckoo clock, the dark-wood furniture, and the heavy, wood-frame TV set that never knew cable. On side tables, she kept a Sooner slag-glass swan bowl and a pressed-glass candy jar always filled with Starlite Mints in both peppermint and spearmint. When the TV was off, she loved to play country music, whether on the radio, vinyl, or cassette tape—from Hank Williams to the Oak Ridge Boys and Alabama to Randy Travis and Garth Brooks. Her tiny kitchen had a Formica table and roosters on trivets and tea towels. One of my earliest memories of the house is my cousin, Bryan, then 10 years old, eating cereal on his Spider-Man TV tray, watching "Dukes of Hazzard" next to the floor furnace, while Grandma sat on the couch, asking for help with "TV Guide" crossword-puzzle clues, nibbling on a frozen home-made oatmeal cookie she had retrieved from a Country Crock container.

Top: This sofa's shape, structure, and colors are almost identical to my grandmother's couch. (Via Coffeesnob) Above: The picture pattern of this wood-frame sofa may be closer to the actual print of Grandma's couch. These types of couches are sometimes billed as "Retro Gauche" or "Coloniawful."(Via Reddit)

The Grandma's Couch meme got me thinking about all the mid-century styles that design-conscious people would like to forget, from the low popcorn ceilings to wall-to-wall shag carpeting. Thanks in part to IKEA and Target, young people today are enamored with Mid-Century Modern furnishings and home goods with their clean lines, dainty teak toothpick legs, bright colors, and quirky-cute Space Age patterns. These trends obviously influence the current market for vintage wares. For example, vintage Pyrex dishes in solid primary colors or the pink "Gooseberry" pattern are hot, while the brown Pyrex pattern my mom has is not. While the '80s have come back in the form of high-waisted jeans, neon colors, and retro radio, no one seems eager to bring back heavy carved wood furniture with brass fittings, conservative blazers with thick shoulder pads, or the brown-orange design palette I encountered everywhere before 1983.

All of this made me ponder: Where did this Grandma Couch—which is somehow both conservative and flamboyant at the same—come from? How did so many people have it, when it is largely ignored by taste-makers obsessed with mid-century design? What did life in the '60s, '70s, and '80s really look like for the squares? What of the people who didn't have the money or inclination to install their homes with all new Modernist furniture, who never embraced countercultural bohemia, who never donned a sparkly shirt to hit the hottest disco?

A 1958 still from the TV series "Gunsmoke" shows Amanda Blake as Miss Kitty and Milburn Stone as Doc Adams. (Via WikiCommons)

I reached out to Pam Kueber, who coined the term "Mid-Century Modest," and runs the blog Retro Renovation, where she advises people who buy mid-century homes how to restore them in a way that actually reflects the period. Could she explain the Grandma Couch?

"Blame it on 'Gunsmoke,'" Kueber tells me with a laugh, referring to the hugely popular Western TV show that aired on CBS for a record-breaking 20 seasons, from 1955 to 1975. "Although, there's more to it than that."

Ah, yes—Westerns. Before World War II, most Americans were still living in rural settings, and very much identified with the pioneers of yore. Grandparents born between 1910 and 1940, if they had electric wiring in their homes, grew up with cowboy heroes such as Tom Mix and the Lone Ranger on the radio. At the very least, they could catch a fantastic frontier shoot-'em-up drama at the local cinema. "Stagecoach" was the runaway hit of 1939, making John Wayne a tough-talking gun-slinging star who would reach the height of popularity in the 1950s and '60s, the years we also associate with future-facing Space Age Modernism. On TV, "Gunsmoke's" prime-time dominance was closely trailed by the NBC mining Western "Bonanza," which ran for 14 seasons, from 1959 to 1973. A couch reflecting rustic prairie life in autumnal tones would have been appealing to the audience curling up to journey to the Wild West every week.

A found snapshot from 1977 shows a grandpa hanging out with his grandkids on a brown-tone floral Colonial-style wingback sofa. (Via eBay)

"During postwar years, we were very much about expansion of America into the West: Phoenix, Arizona, and Houston, Texas were exploding," Kueber explains. "All of Texas and California were growing, growing, growing, growing, growing. So all things 'Western' were huge, from ranch houses to denim jeans. Along with that come all these Old West motifs in furnishings. My Grandma and Grandpa loved those Western TV shows when I was young. People were coming off the farm, too, like my grandparents, who moved their family from the farm in North Dakota to the suburbs of Southern California in the '60s. In my attic right now, I literally have an ox-yoke mirror that came from North Dakota. Grandpa took this farm implement and upcycled it. It's a part of America's farming, pioneering heritage. But what am I going to do with it? I can't sell it now. I can't even give it away."

"I will go to my grave saying most people—modern people—do want unnecessary decoration. We are decorative beings."

During the Depression, my grandma's family owned a general store near Jay, Oklahoma. My great-grandfather took so many IOUs that he went broke and the whole family had to work as sharecroppers for a grim period. Grandma met Grandpa at a square dance in Tahlequah. He served in World War II, while she took a clerical job at a home-front factory. They married when he returned from the war in 1946, and lived in Tulsa. Theirs is a hardscrabble all-American working-class story, but their photo albums reveal the days grandfather was making good money on the assembly line: Grandma posed in smart, blazered '40s dresses near a streamlined classic car and outside the fashionable Kress department store in downtown Tulsa. Still, even though they lived in a city, I believe my grandparents always saw themselves as humble country folk.

But there's so much more going on with these sofas than the country-home themes, the shabby barns, red and brown leaves, mantel clocks, or horses on the prints. While Kueber and I weren't able to nail down an exact year or a maker, she was able to help me put the Grandma Couch into context.

Depending on the meme, everyone—or everyone's grandma—had this sofa. Here, the busy pattern on the synthetic velour includes an old-timey clock. At least, I think that's what's happening.

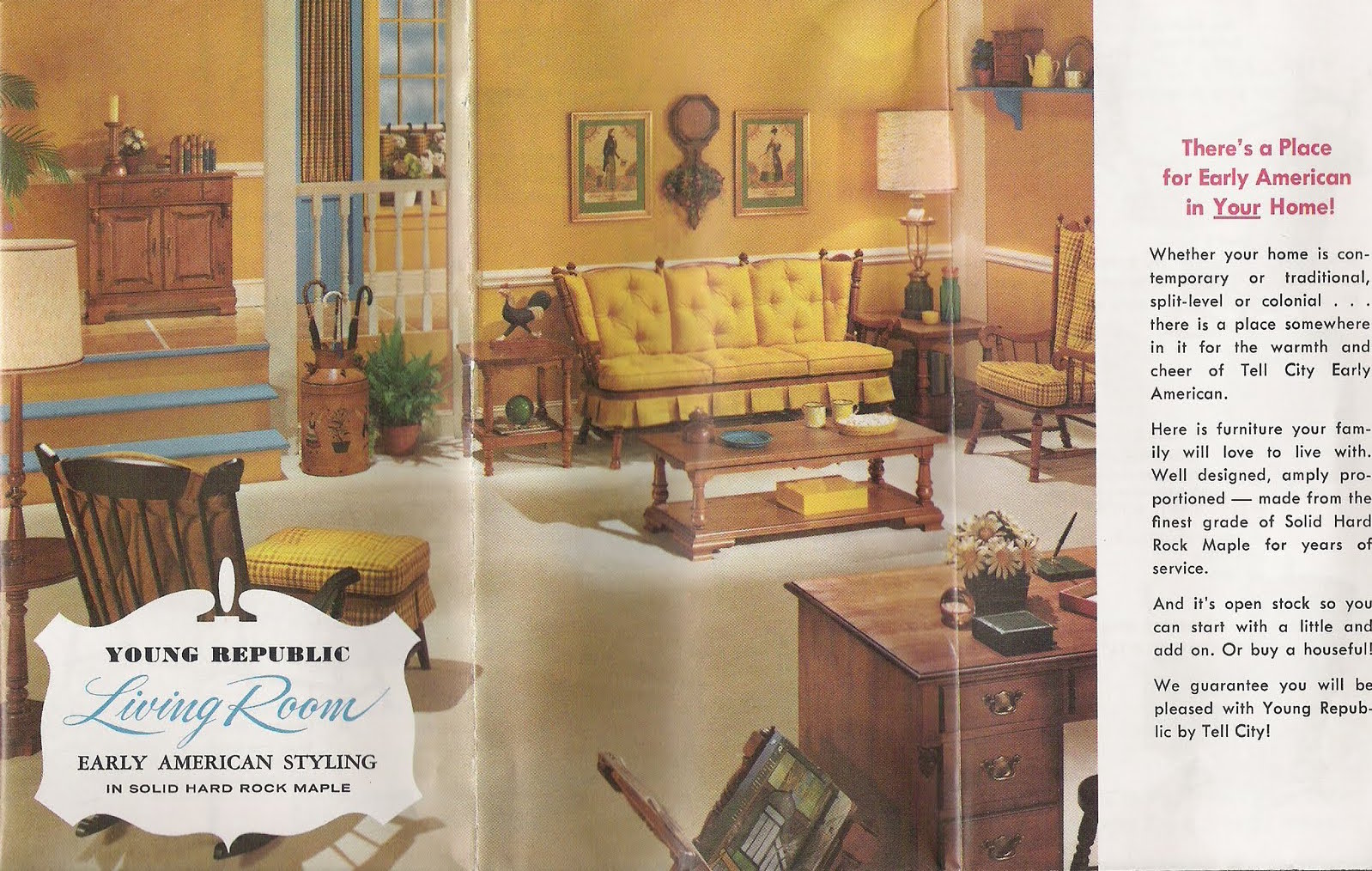

"This couch is a hat tip to Early American or Colonial Revival décor, which was massively popular through most of the 20th century—married to an indestructible, essentially plastic Space Age fabric, which our grandparents would have found appealing because our grandparents didn't tend to redecorate constantly," Kueber explains. "They had one sofa. They bought their furniture on a layaway, and by the time they found enough money for a sofa, they wanted it to last forever. So the good news was that fabric was going to last forever—but the bad news was that fabric was going to last forever.

"I say that in a loving way: They got the fashionable look of the day, which was this novelty print on their sofa, and it was made from a fabric that had all the modern qualities that one would want. So, hooray! I'm sure it was a big day when that sofa came home."

The first iteration of Colonial Revival originated around 1876, when Victorians were celebrating the United States centennial, and the throwback interior style—which sought to shed the frilly excesses of cluttered Victorian neo-Rococo fashion—remained popular up to 1940. It branched off into two larger design subsets: 18th-Century Colonial Revival and Early American. The former embraced the stately, symmetrical style seen in the homes of the Founding Father elite—the exteriors defined by red brick, white shutters, and maybe symmetric neo-Classical columns; the white-walled interiors a combination of elegant, scrolling Georgian and Neo-Classical upholstered wood furnishings and gold-trimmed mirrors. Early American is more about the hard-working pilgrims, farmers, and pioneers in their log cabins and farmhouses with heavy, simple wood furniture.

The "floral sofa" in this Sears Open Hearth Country Home ad, which appeared in the May 1977 issue of "Redbook," is the closest advertising image I've found to the Grandma Couch. (Via classic_film on Flickr/Creative Commons)

The two styles are cousins, connected by a sentimental, patriotic nostalgia for the birth of this country, and probably a lot of overlap such as Windsor chairs and other turned-wood pieces. In the early 20th century, Wallace Nutting made a name for himself building fine wooden reproductions of Colonial furniture, for example.

After the tumultuous years of World War II, Colonial Revival, and particularly Early American style, had another rebirth, popular among young families who wanted a return to tradition. The grandma factor is practically built in—even as a young woman, grandma wanted the furniture her grandma had.

"The Colonial Revival style endured, but it took on different forms over the years in post-World War II America, which is what I tend to write about and focus on at Retro Renovation," Kueber says. "In the '50s, the style looks more like it looked in the '30s and '40s because we were still recovering from the Depression and World War II, so there were carryovers. By the '60s and '70s, you started to see more marketers reimagining and playing with the concept of what Early American meant."

An early '70s kitchen in Arizona with a patriotic eagle, Knotty Pine cabinets, modified Windsor chairs, and a Harvest Gold and Burnt Orange color palette. (Via Ugly House Photos)

Kueber says her grandparents had a similarly unforgettable home as my grandparents', but their family-room couch was covered in a popular plastic-based plaid marketed as Herculon in Sears catalogs of the '60s and '70s in the same drab color palette. The walls were covered in a type of Early American wood paneling known as Knotty Pine.

"Grandma and Grandpa had a small ranch house in Oceanside, California," she recalls. "Every week, we visited their very memorable home, which had a swimming pool and a tangerine tree in back. They had a Knotty Pine family room, too, right next to the wood-paneled kitchen with the Early American cupboard, where Grandma kept her big salt-and-pepper shaker collection. Grandpa would offer us those Orange Slices, that jelly candy with the sugar coating. It was a very prototypical '60s Grandma and Grandpa house.

"Knotty Pine walls and wood paneling were everywhere because Grandpa and Dad were still finishing rooms themselves," she says. "So my dad put a lot of wood paneling in our houses all the way through to the last one they built together, which was in '71. The wood paneling would've gone well with these Herculon sofas. I don't even know what Herculon is, but it sounds really durable, doesn't it? These sofas probably weighed a ton, and were probably well-made, with eight-way hand-tied springs and dovetailed everything. At that time, every piece of furniture a family purchased was a big deal."

On the right side of this 1970 image of a Montgomery Ward floor, you can see a brown floral couch similar to my grandma's, as well as a Colonial Revival coffee table that resembles hers, but with different hardware. In the background is an orange plaid couch. (Via Pleasant Family Shopping)

Also, Kueber explains, houses got bigger from the late '60s to the early '80s, and Americans got bigger, thanks to all the food we had access to in the postwar prosperity. As a result, furniture got heavier and bigger. Cabinet and dresser styles I've found in '70s Sears catalogs—often dubbed "Mediterranean" and "Spanish"—feature the faces of drawers and doors densely adorned with carved wood. In an illustration of a '70s Montgomery Ward sales floor, I see a floral-print couch with the same architecture as my grandma's, paired with a piece that looks like her Colonial Revival coffee table, which was open on the sides with turned-wood supports, and had a double-door cabinet in the middle. She kept our coloring books and crayons in the cabinet, while the coasters that had to be used for cans of pop were stashed under the sides. I remember running my finger over the planed wooden face of the cabinet, and how the ornate pulls would sometimes come loose and turn askew.

"We were better fed than our grandparents," Kueber says. "Grandmas are like 5'1"; I'm 5'9". So people started to need bigger sofas. As homes got bigger, you saw a move during those years toward heavier furniture with more wood embellishments, like Mediterranean furniture of the era, which has lots of gewgaws carved into it every which way. This sofa had that same kind of heaviness to it, and again had pieces of dark wood like oak showing. The kitchen in these bigger homes might open to a family room, while the formal living room would be sequestered off and rarely used. I associate these novelty-print sofas with the family room, which could be woodsier and more casual, with shag carpeting. And brown, lots of brown; everything was brown."

This 1970s catalog page shows Spanish or Mediterranean style furniture, heavy with carved wood gewgaws. (Via Pinterest)

So how did brown become the color du jour of the late '70s? Well, as consumerism exploded in the postwar years, home furnishings marketers took a cue from Alfred P. Sloan of General Motors, who came up with the idea of tweaking car models just enough every year that Americans would covet a new car. Department stores and furnishing companies also began to change up their furniture and home décor offerings each year, presenting the "most current" colors and patterns in their catalogs and magazine ads. "Everything you bought became fashion," Kueber says.

"Our grandparents didn't want an ugly couch; these were seen as beautiful and stylish."

In the 1950s, women were encouraged to embrace ideas of traditional femininity, which included a return to homemaking. While the '50s housewife was focused on rearing the kids, she was also encouraged to shop and literally "make" the new suburban home. That, taken with the sunny postwar optimism, led to pastel-colored Princess phones, pink and turquoise bathroom tiles (also given a nod by TipHero), and sunny yellow kitchens. "Historian Thomas Hine dubbed this style Populuxe, referring to the pastel lollipop colors of the 1950s," Kueber says. "Everyone talked about that era's sense of exuberance."

As youthful Mod fashions came to the United States in the early '60s, you saw housewives taking even more risks with bright daisy prints in vibrant reds, bright oranges, and lime green. But then, the American mood took a grim turn. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, and civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on April 4, 1968. The United States was sending more and more young men to fight in the Vietnam War, and their deaths led to turmoil and protests including the "Flower Power" anti-war movement. Around the same time, the counterculture opposing the war was promoting a more anti-consumeristic ecology-friendly lifestyle known as the Earth Movement. Ironically, marketers saw dollar signs in the new looks created by the youth culture and, in the early '70s, started offering furnishings in bright psychedelic patterns as well as muted "earth tones."

In this 1970s ad, a stylish young woman holds a book on a floral Grandma Couch while an unseen companion pets her golden retriever, who rests on shag carpeting surrounded by Colonial Revival furniture. (Via The Giki Tiki)

"In the '60s, America sobers up and matures; and those sociological factors were thought to influence color palettes," Kueber says. "Today, a lot of people are trying to correlate or ascribe historical events to changes in American color palettes or fashion preferences. Who knows whether it's really true. Did the market want earthier colors and patterns, or did the marketers glom onto the Earth Movement and make the market want it?

Some people tried drugs or hosted swinging sex parties; others channeled their sense of adventure exclusively into garish upholstery.

"There were echoes of big color in the '70s, remnants of the '60s Flower Power," she continues. "On Retro Renovation, we've looked at some '70s furniture that is all orange or all lime green, which were big Flower Power colors. Whereas, I want to say Avocado and Harvest Gold started between '66 and '68, introducing drabber colors to the market. That's what led to the gold, brown, and orange tones of this sofa, which is also more drab than the '50s palette. Those Harvest Gold and Avocado were ginormous, powerful trends that lasted at least a dozen years."

A Getty Image taken by Steve Errico (which you can see here) shows a brown-tone floral-print couch similar to the Grandma Couch in the context of a '70s living room. There's heavy but lightly printed beige drapery behind it; a splotchy brown, tan, and cream pattern carpet; dark wood paneling on the wall; a Colonial Revival coffee table with turned-wood legs; a rustic field-stone fireplace with something looking like an eagle on the mantel; and a wood chandelier that's not a repurposed wagon wheel but a ship's wheel.

The Spring/Summer 1976 Sears catalog shows a family touring the home of Founding Father John Adams in Quincy, Massachusetts. (Via eBay)

The United States Bicentennial in 1976 prompted an explosion in Americana, including Early American and Colonial Revival furniture. The cover of the 1976 Sears Spring/Summer catalog shows a family of four posed at the Quincy, Massachusetts, birthplace of Founding Father and second U.S. president, John Adams. A flag waves against the blue-sky backdrop of the red-painted wood Colonial home. Inside the catalog, you can find plenty of furniture like Windsor-style chairs, plaid "country style" couches, and heavy-wood furniture lines branded as Early American and Colonial Style—including the Sears Open Hearth Country Home line. The corniest products of 1976 are known as Bicentennial Chic and came in the colors of the American flag with overt American symbols incorporated into the design. The catalog contains leather-covered bars with eagles and shields embossed into the front and bedspreads in "patchwork" and red, white, and blue patterns.

Why were these trends so universal? "My sense is that back in the day, the color and fashion trends lasted longer," Kueber says. "Again, it goes back to 'Gunsmoke' and 'Bonanza.' Even though families were starting to get cable in the 1980s, up until 1990-something, three major TV networks still dominated American TV. Before the '80s and '90s, we all watched the same mass media. We all watched the same major motion pictures. There were seven ladies' magazines, meaning millions and millions of people were looking at the same ads for the same stuff. The internet didn't even really work until 2010—not really. So there was a common culture, and true mass market you could sell to. We all bought the same colors and trends.

"Nowadays, fads are splintered a thousand ways because no matter what you're into, you can find your own community that's into that, too, on the internet," she continues. "Even my community, which I've carved out of a niche, is made up of people who like the same offbeat vintage stuff. I don't focus on upscale, designer Mid-Century Modern. It's more of a community for thrifters."

Another 1977 ad for the Sears Open Hearth Country Home furniture line. Tartan plaid made of indestructible synthetic weaves, Windsor chairs, red tile, braided rugs, and patriotic colors were all a part of the "Spirit of '76" Colonial Revival. (Via Flickr)

Because Early American furnishings were largely recycled ideas, only updated with technology and materials developed for the war, these time-worn styles don't excite design-history junkies, who love everything cutting-edge and game-changing. Perhaps the relentless focus on clean-lined Modernism gives us a skewed version of what American homes looked like in the late 20th century.

"In my attic right now, I literally have an ox-yoke mirror that came from North Dakota. What am I going to do with it? I can't even give it away."

"I don't think Mid-Century Modern was popular at all," Kueber says. "Postwar Americans liked Center-Hall Colonials with traditional furniture like Early American décor, with a little bit of French Provincial maybe thrown in there. But then Early American sort of goes sideways into the '70s, like with this novelty-print couch. Still, Mid-Century Modern is about the absence of unnecessary decoration. I will go to my grave saying most people—modern people—do want unnecessary decoration. We are decorative beings."

The philosophy of Modernism goes back as far as 1880, around the time of the Arts & Crafts Movement, which promoted simple lines and hand-crafted, minimally decorated furniture as a response to the chintzy, cheap furniture produced in Victorian factories. In the early 20th century, Germans thinkers in the Bauhaus School merged the machines of mass-production with the clean lines of Arts & Crafts. In 1925, Swiss Modern-architecture pioneer Le Corbusier declared: "Modern decorative art has no decoration."

"Around 1939, the men and women who were fleeing Nazi Germany came to America, bringing Modern design ideas like Bauhaus," Kueber says. "Their influence led to what we call Mid-Century Modern—a term coined by Cara Greenberg in 1984—which included the Case Study Houses with these sleek, long, low sofas and tulip chairs that were very opposite of highly decorated furniture."

The iconic Case Study House No. 22 was designed by architect Pierre Koenig for Clarence "Buck" Stahl and built in the Hollywood Hills in 1959. (Photo by Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles)

The Case Study Houses were a series of experimental homes funded by "Art & Architecture Magazine," between 1945 and 1966, and designed by major Modernist influencers including Richard Neutra, Raphael Soriano, Craig Ellwood, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, Eero Saarinen, A. Quincy Jones, Edward Killingsworth, and Ralph Rapson.

But if you and I hopped into a time machine to our parents' and grandparents' worlds of the 1950s and early '60s, we wouldn't be in an all-Modern-all-the-time world. At Retro Renovation, Kueber has spent the past 12 years helping people find period-appropriate materials to restore their mid-century homes, and has learned a few things about what the design of the era really looked like, thus her "Mid-Century Modest Manifesto."

"Mid-Century Modest is the counterpoint to this notion that right after World War II everything was Mid-Century Modern," Kueber says. "My sense of looking back at design history of postwar era was that the masses of America were not buying that stuff, nor were they building Case Study Houses, which were, in and of themselves, pretty impractical. Most of America was steeped in a Colonial Cape Cod house ideal. The home in the 1948 film 'Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House' was a Colonial Revival house.

An article in the September 1958 edition of "Family Circle" extols the virtues of affordable Colonial Revival and Early American furniture. (Via Flickr)

"I say in the Mid-Century Modest Manifesto, maybe a million people had those fully Modernist houses. For every million people who had one of those, tens of millions of Americans had a more traditional home. Even in the new suburban ranch-house layouts, the majority of American homes and the stuff in them were what I call Mid-Century Modest, which was more like what we're talking about, what your grandma had with her Early American furniture and sofa. They came from farms. They wanted something more conservative, traditional, practical. And they liked Early American décor.

"My mother-in-law, who was a high-end decorator, also had very traditional décor in the late '50s and early '60s," she continues. "She says all of her friends who bought Mid-Century Modern regretted it and got rid of it as soon as they could. It was too limiting and specific. So she liked having a more traditional décor that you could play around with. You could change out the fabric. She would be one to change her draperies and her pillows, for example, to be more trendy."

Speaking of fabrics, the wackiest aspect of the Grandma Couch is the Old West picture-pattern upholstery. It's weirdly similar to Victorian wallpaper with the same idyllic scene over and over again—the sort of wallpaper disdained by British textile designer William Morris, who was one of the leaders of the spared-down and elegant Arts & Crafts Movement. While couches with plaid and floral prints were all over the place in the late 20th century, this rustic-image fabric is something that seems very specific to the '70s: When "Gunsmoke" and "Bonanza" where winding down and headed to syndication-land, "A Little House on the Prairie," which debuted on NBC in 1974, made the pioneer life of Laura Ingalls Wilder seem romantic. Suddenly, Americans were snatching up modest calico dresses from Laura Ashley, Jessica McClintock's Gunne Sax line, and so on.

Game birds roost among wildflowers on this fake-velour '70s Grandma Couch. (Pinterest)

"I don't think that novelty prints on sofa fabrics have been very popular throughout history," Kueber muses. "Clearly, it was an experiment promoted by sofa manufacturers as a new look. And yes, for some number of years, customers went for it. But it didn't endure."

Repeating patterns were more common on wallpaper because it was a relatively affordable and temporary way to make a room more interesting, Kueber says. "If you look at pictures from the '40s and '50s, you'll see houses weren't so chockful of stuff; people didn't have a lot of furniture or art on the walls, so the homemaker would choose lively patterns," she explains. "Until the introduction of latex wall paint in the post-World War II era, to change the color of the wall, you had to put really noxious oil paints on it. They took days to dry and were nasty with lead and other toxins in the mix. You really had to hire a professional to put that stuff on your walls, but it lasted forever.

"It was cheaper and easier for Mrs. America to just put wallpaper up," she continues. "I don't know that Mrs. America necessarily changed wallpaper often, but she could. You do hear stories about people going into older houses, moaning that they had to strip off seven layers of wallpaper. So wallpaper was marketed as more of a fashion product that you could change out over time, cheap and cheerful. But a sofa is not typically viewed as a cheap and cheerful purchase. It is a lifetime purchase."

A young dad cuddles with his baby on a Colonial Revival sofa with a brown Herculon plaid fabric in this 1979 vernacular photo. (Via eBay)

The '70s, however, was a time when everyone, even the Western-loving square, was more open to experimenting in some way. Some people tried drugs or hosted swinging sex parties; others channeled their sense of adventure exclusively into garish upholstery.

"In my mind, the '70s was the most fantastic decade for décor because designers were just doing the craziest things," Kueber says. "The design world had incredible energy. The decade was the last great gasp of frenzied sexual revolution, pre-AIDS. You could do anything. It was like there were no repercussions—until there were. Then we had the rise of the yuppie and The Preppy Handbook. Oh, my God, what a comedown that was. Honestly, I think the Grandma sofa is of that wild 1970s experimental ilk, too."

Interior design goes through both evolutionary and revolutionary changes, Kueber explains. "With General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan would first alter the car's tail fin, and then the headlights, and within a couple years, it's a completely different car. But you didn't really notice the changes as the years went by. Then sometimes design changes in a totally revolutionary way, where the pendulum abruptly swings the other direction. Somebody decides to shake things up and go in the completely opposite direction of what's popular, and it resonates.

Pam Kueber's favorite "Bicentennial Chic" room from a mid-1970s Ethan Allen catalog. (Via Retro Renovation)

"Changes in Early American and Colonial Revival are more evolutionary, like Sloan's automobiles," she says. "I'll say, 'Oh, I can see what they did. That's a take on Early American over there but they changed the color and the scale.' My daughter is getting an apartment, and I was showing her Ethan Allen furniture, which is a classic Colonial Revival company. Today, they're offering this black lacquer cannonball bed, but they have totally blown up the scale of it. Clearly, it has Early American or Colonial Revival roots, but it's fresh and modern."

Today, prairie fashion is making a comeback, as thrifters are hunting for prim Laura Ashley dresses with high neck lines, puffy sleeves, and big bows. And of course, we can't talk about prairie style without mentioning the incredibly influential HGTV show, "Fixer Upper," which ran from May 2013 to April 2018, featuring the Waco, Texas, based remodelers Chip and Joanna Gaines. Their so-called Farmhouse Chic style featured on each episode of "Fixer Upper" has taken over in a big way, but it looks very different. The goal of "Fixer Upper" is to make these old houses look light and airy with minimal patterns, as opposed to the dark-wood, drably earth-toned, and pattern-dense look of the '70s "country style" living room. Although, there are similarities: "Shiplap is Knotty Pine hung horizontally and with no amber shellac on it, isn't it?" Kueber muses. "Call me crazy, but I think that's what that is."

This 1952 ad for Formica countertops shows the modern material paired with Knotty Pine cabinets and paneling. The ad text promotes "the warmth and charm of the early American kitchen." (Via Retro Renovation)

That said, there's no place for the Grandma Couch in the Gaines' tasteful world with its distressed-paint antiques and repurposed farm gear. "Looking at this sofa today, I struggle to picture how you could integrate this successfully into a room you'd be happy living in your entire life, as opposed to something ironic," Kueber says. "But I think there are other elements of the era that we might see revived big-time, like plaids. Even stuff like the drab colors, the Avocados, we keep seeing come back in fits and bursts. It's a great color. Golds and oranges are great colors.

"In fact, we're going to probably come up on another Colonial Revival soon because, as one of my readers recently said, 2026 will be our 250th anniversary of the Independence," she continues. "Colonial Revivals often come during those big anniversaries. Millennials want to do the opposite of whatever their mother did, and maybe more like what Grandma did. They love Grandma, but they must disengage from their mother. Millennials might kind of like some Colonial motifs like cannonball beds. There's nothing wrong with them. They're beautiful."

As for the Grandma Couch, it is not just snubbed by the Gaines and the high-brow coastal elite; it regularly wins low-brow online competitions for World's Ugliest Couch. However, over at Retro Renovation, insults like "ugly" and "hideous" are not allowed. In fact, my mom tells me that when my grandparents purchased the sofa in question, they were so proud they were able to pay for a brand new couch and not use a hand-me-down for the first time in their lives.

Christine's Creations in Woodstock, Georgia, upcycled this grandma furniture set into stylish outdoor furniture. But who's to say how long apple green and apple red will be en vogue? (Via Pinterest)

"That's why we shouldn't make fun of it today," Kueber says. "Blogging at Retro Renovation over a dozen years, I have seen so many fashion fads in décor that people today make fun of, but were very fashionable at the time. Our grandparents didn't choose them because they wanted an ugly couch; they chose them because they were marketed as the fashion of the time and they were seen as beautiful and stylish. It's the old 'beauty is in the eye of the beholder' trope.

"I'm sure that there are sofas being purchased today that are considered very au courant that will be memed viciously 10 or 20 years from now," she continues. "So be careful: If you don't want your sofa memed in short duration, choose something that's not too specific, that's not too 'of the moment.' Aim for a timeless look."

What's surprising about the TipHero list and even the "Everyone's Grandma" meme is how sweet they are, made with an earnest love of grandmas and their hard-candy-filled homes. Recently, 47-year-old comedian, actor, and rapper Mike Epps posted a meme about "What Being Sick Looked Like in the '80s" on Facebook. It included Campbell's Chicken Noodle Soup (check), saltine crackers (check), Vick's VapoRub (check), "The Price Is Right" (check), ginger ale (sometimes, but usually 7Up)—and another variation on the Western-themed fake-velour Grandma couch. This "ugly" couch with its hard arms and scratchy fabric has become a symbol of cozy comfort and healing love.

A Grandma Couch meme shared by comedian, actor, and rapper Mike Epps on Facebook.

In fact, on eBay, I've found Polaroids and snapshots from the '70s or '80s of actual grandmas and grandpas with their actual grandchildren cuddling on the Herculon plaid and the earth-tone floral Colonial-style sofas. They are adorable in a way that makes you want to cry, rather than laugh.

"Maybe the fashion didn't last—we all make mistakes," Kueber says, admitting that the first impulse most young people have is to mock the Grandma Couch. "But when you marry the sofa with the hard candy, the whipped cream on every piece of pie, and the wave 'Goodbye,' then suddenly you just can't help but love that couch. Many people have great memories of being in their grandparents' house, so that sofa becomes part and parcel of those memories. You don't want to make fun of it because it was all about the love—and that's what we make homes for."

Source: https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/it-came-from-the-70s-the-story-of-your-grandmas-weird-couch/

0 Response to "Montgomery Ward Vintage 1970s Suit Dark Blue Red"

Post a Comment